The Blues Is Alive And Well In ‘Sinners’- Just Look Out For Those Bloodsucking, Dirty-Talking Vampires

By Bennett Kelly, music journalist and author of Sensation Blues

Blues music, born of the Mississippi Delta, has sometimes traded in devil mythology, and “Sinners”’ evil is apparent in its opening scene: it’s Sunday morning, October 16, 1932 in Clarksdale, Mississippi, when Sammie Moore limps into his father’s church mid-hymn.

In bloodied, tattered clothes, Sammie wields like a war club the broken neck of an acoustic guitar. (Later we learn it’s a beautiful black and silver resonator, possibly won off Charlie Patton, the lone real-life bluesman we recall getting a shout in the film.)

Pop pleads with him to drop it, and to leave his sinning ways behind, setting up the classic good vs. evil, preacher-bluesman dilemma: “You keep dancing with the devil, one day he’s gonna follow you home,” warns the father.

With the scene set, we cut to sunrise the morning prior, where we find Sammie (played by Miles Caton) intrepid: he’s already picked his cotton quota for the day, before anyone else has even started, so that he can go juking with the Smokestack twins, his prodigal older cousins (played by Michael B. Jordan) who’ve returned home from Chicago where they learned a few tricks as Capone henchmen.

Smoke and Stack enlist Sammie’s help in rounding up supplies and manpower, and for him to star at their new juke joint this evening, in a barn-sized sawmill on the outskirts, purchased with duffel-bag cash.

Terraplaning through the cinematic countryside, they amble downtown and run into former flame Mary (Hailee Steinfeld), who delivers a line that would make even Robert Johnson blush.

Furthering the “Smokestack” homage, they also pick up a Howlin’ Wolf-esque character at the depot to pair with Sammie, and off they go into the juke joint night.

***

The bustling Clarksdale and train depot scenes in “Sinners,” filmed in Louisiana and with several locations enhanced by CGI, don’t typify dust-bowl era imagery.

But they aren’t unrealistic – Clarksdale in the Great Depression was a relative oasis for the era – emphasis on relative and for whom – a business thoroughfare getting by on the cotton trade.

Clarksdale’s Delta Avenue, presumably the inspiration for the downtown scenes, has a largely unchanged architecture from then, offering its visitors a unique step back in time.

Today, the town has “More characters than Sesame Street,” said Visit Clarksdale director Bubba O’Keefe to our Danny Coleman. O’Keefe has helped evolve Clarksdale’s downtown from lights-out to international blues destination over the last two decades.

Now Clarksldale is like a blues heaven, however oxymoronic that may be. It’s a gritty Disney World for blues fans with no b.s., only blues. At least that’s how it looks for the weekend trippers like myself. The rest of the time, it still maintains a 40% poverty rate.

***

“Sinners”’ decade was the pinnacle of country blues. The genre’s fashions and songs are influential as ever, which the movie keenly illustrates during one musical scene at the Smokestacks’ Club Juke.

In 1932, when “Sinners” touches down, Robert Johnson (1911-1938) and Son House (1902-1988) were at the height of their powers and prowling all over Mississippi and beyond, especially Johnson.

As was Charley Patton (1891-1934), the first father of the blues, who played a New York City festival in the year of his death. Later in the decade, Johnson too was sought out for a New York showing, at Carnegie Hall, with the promoters discovering his untimely death only when they went searching for him.

In 1932, nineteen-year-old McKinley Morganfield, aka Muddy Waters (1913-1983), was playing blues on Clarksdale’s Stovall Plantation. The famed Alan Lomax-Library of Congress recording sessions of him would come in 1941.

Hearing his recordings played back helped Muddy know he could do it; he subsequently moved to Chicago in 1943 and became the king of Chicago blues, if not blues everywhere.

Thus 1932 is a sturdy, bluesy year for director Ryan Coogler to have staged “Sinners.” But in search of further clues for the specific date, we went combing through the archives.

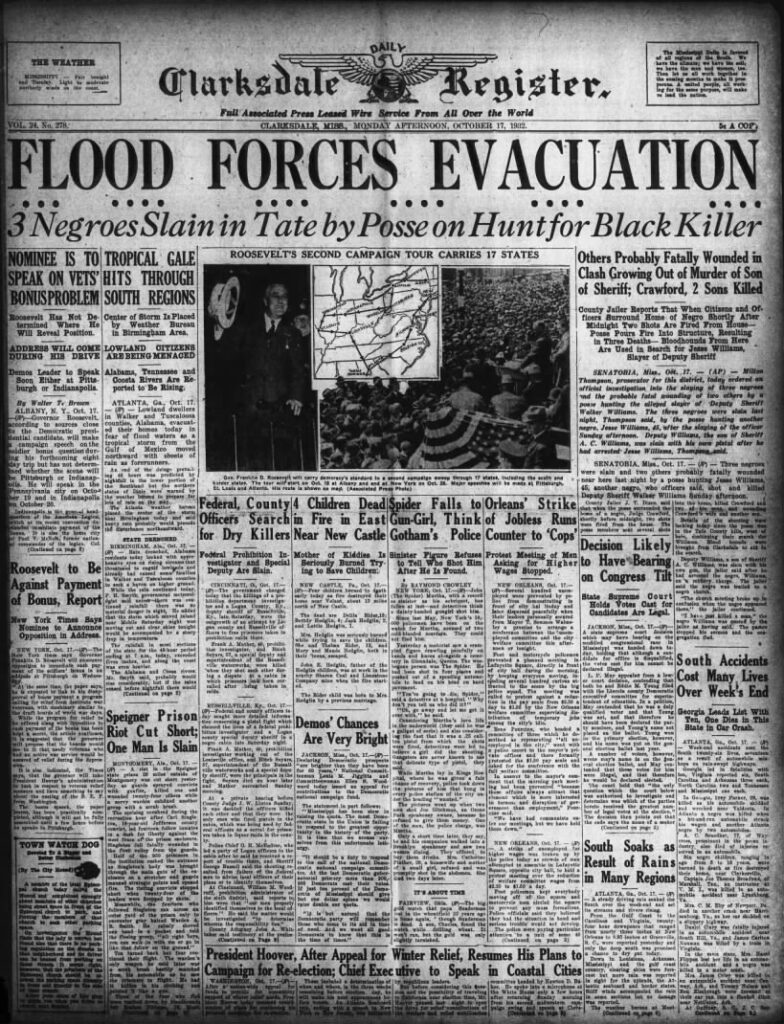

The Clarksdale Register newspaper of October 17, 1932, the Monday after the events of the movie take place, offers a very real parallel to the fictional horrors.

The headline describes a manhunt in Senatobia, Mississippi, an hour northeast of Clarksdale, that resulted in the slaying of “3 Negroes” – collateral damage in the search for a man wanted in the killing of a sheriff deputy’s son.

“Three negroes were slain and two others probably fatally wounded near here last night,” reads the AP dispatch, “by a posse hunting Jesse Williams, 45, another negro, who officers said shot and killed Deputy Sheriff Walker Williams Sunday afternoon.”

Earlier Sunday, the deputy sherriff was “shot to death when, the state charged, he sought to arrest the Negro on a minor charge,” reads a later AP chronicle.

“Deputy Williams, a son of Sheriff A. C. Wlliams, was slain with his own gun, the jailer said after he had arrested the negro, William, on a robbery charge.”

A later April report described “The tragedy which aroused the entire county, occurred last fall in the new Salem community when Deputy Williams, assisting his father in an investigation of a robbery, went to the home of Jesse Williams to question him in regard to the stealing. While talking to the negro he was fired upon by [Williams’ son] Steve with a shotgun. When the young deputy turned to see who was doing the shooting, the older negro snatched his pistol and began firing.”

“The jailer said the negro was trailed to a negro church. The church meeting broke up in confusion when the negro appeared there,’ the jailer continued.

“‘I have just killed a man,’ the negro Williams was quoted by the jailer as having said. The pastor stopped his sermon and the congregation fled.’”

Later that evening is when the “posse pours fire in the structure”: “County Jailer J. T. Dixon said that when the posse surrounded the home of a negro, Judge Crawford, shortly before midnight, two shots were fired from the house. The posse members sent several shots in the home, killing Crawford and two of his sons, and wounding Crawford’s wife and another son.”

Bloodhounds were brought in from Clarskdale to search for Jesse Williams. He escaped into Memphis, Tennessee, where he was eventually arrested in December.

Jesse Williams was tried in February and sentenced to death on June 9, 1934, Tate County’s “first legal hanging” in twenty-five years.

“The Negro spent his last days reading the Bible and singing hymns,” reads that final report.

“Sinners” is violent, and there is a Klan presence. The movie’s primary villains however are Irish vampires, who serve as a layered allegory for a predatory music industry.

The comfort for “Sinners” viewers is that vampires aren’t real. It’s just that the Clarksdale Register’s manhunt lays bare that fake teeth aren’t needed to show the harrowing stakes of the times.

***

While not a perfect movie, “Sinners” largely delivers. It forges a vibrant blues world like no other, and is a must-see for blues fans.

It’s a horror flick, but not one drowned in frivolous frights and jump-scares. Though bloody, it treads more in psychological drama.

Musically and aesthetically, it’s all there. Miles Caton’s blues stand out, with vocals that strike the smooth tones of modern Clarksdale star Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, who scores a cameo himself.

Stay through the credits, and you’ll be treated similarly to 2019 Beatles-fiction flick “Yesterday.”

And if you’re a blues fan put off by horror in general, see this one anyway knowing that it won’t beat you over the head too badly with a silver hammer, or with a resonator.

Well, be prepared for some gore. Those vampires gotta eat, too.