By Jay Sweet

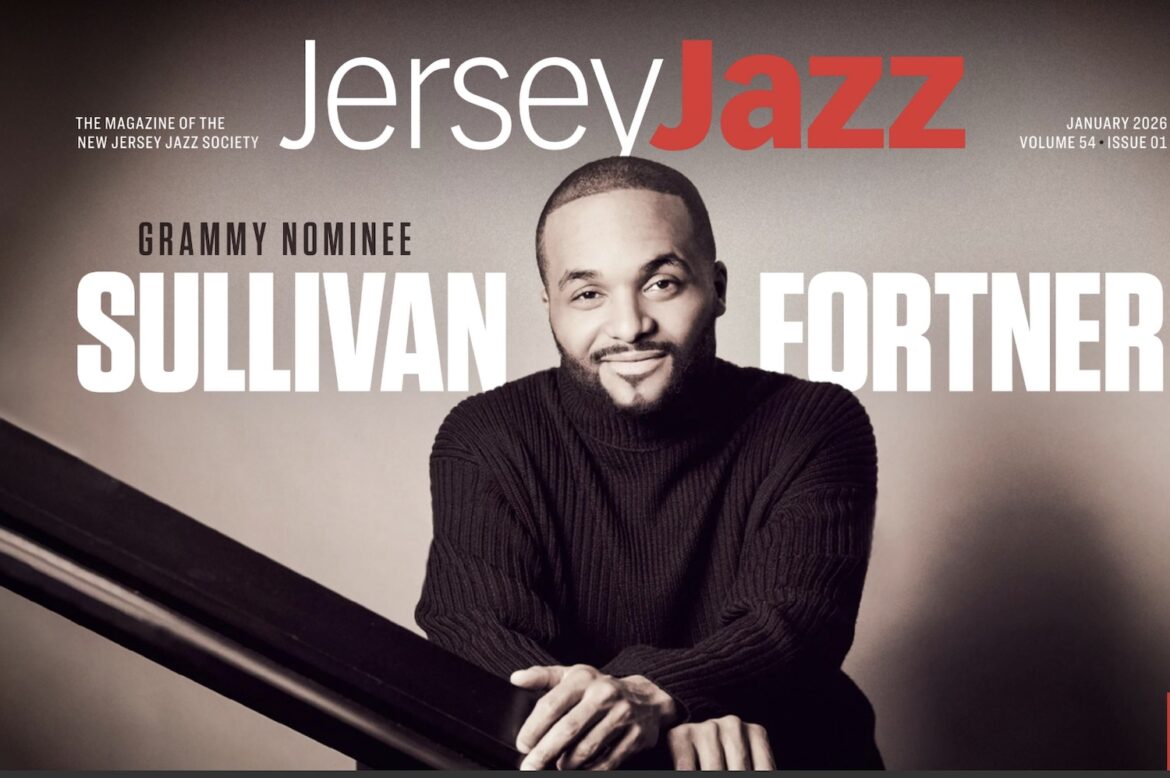

Initially published in New Jersey Jazz Society January 2026, Volume 4. Issue 01

Sullivan Fortner is one of the finest, most sought-after, and most creative jazz pianists on the scene today. The year 2025 has been monumental for the pianist, marked by the release of his Grammy-nominated album Southern Nights (Artwork Records) and appearances on Theo Croker and Sullivan Fortner – Play, Kurt Elling & Sullivan Fortner – Wildflowers Vol. 1 (Edition Records), and Lauren Henderson’s Sonidos (Brontosaurus Records). In addition, Fortner was named the first-ever jazz recipient of the Larry J. Bell Jazz Artist Award, established by The Gilmore Foundation and accompanied by a $300,000 prize. Despite this extraordinary run of success, the pianist remained cool and unassuming as he reflected on the year. Our discussion began with Southern Nights.

“The Village Vanguard asked me to do a week, and it happened to fall over the Fourth of July. They wanted me to put together a special band. The problem was, I didn’t really know how to put bands together, so I was thinking, How do I do this? I just kind of went at it instinctively. Earlier that year I had run into bassist Peter Washington, and I said, ‘Look, man, I’ve got this week at the Vanguard. Are you free?’ He said, ‘Yeah, I’m free. I’d love to.’ So I thought, great—bass player covered. Then I had to figure out the drums. I started throwing some names around, and finally I said, ‘You know what, I’ll just bite the bullet and call Marcus Gilmore.’ He picked up and said, ‘Yeah, man, I’m in town. I’m not doing anything. Of course I’ll play it.’ That was a huge relief. Then I got nervous—especially when Marcus mentioned that he had never played with Peter, and that they’d never even met. So literally, the first night of that week was the first time they ever played together. We hit the first few notes, and immediately I thought, “Okay, ts going to be really good.”

“By Wednesday night, I started thinking about recording. I wanted to record live at the Vanguard, but with that short notice they wouldn’t allow it. So I started calling around to see if any studios were open. Sear Sound Studios had an opening that Saturday morning, around 11 a.m. I booked it and the band came in. We just played what we had been playing all week. One session, about four hours, and we were done. Everything was basically two takes, and most of what made the record was either the first or second take. We laid it down, then went back and played the Vanguard that night. The record is really just a snapshot of that week—of that moment we had at the Vanguard.”

“Overall, I wanted the week and the recording to feel relaxed. I chose tunes that were familiar enough that we didn’t need charts, or could at least take our eyes off the page. That’s how I like to work. I don’t really enjoy playing sheet music. Part of that is because I’m not the greatest sight-reader, but more importantly, every band I’ve learned from or been part of learned everything by ear. There was never any sheet music. For some reason, that approach brings a different kind of life to the music.”

I then asked him about his recording with the great trumpeter Theo Croker. “Theo Croker and I did a duo project—this was probably in 2024. Theo called me, and we’ve known each other forever. We were actually roommates at Oberlin when we were students. We’d been talking for a long time about recording just the two of us, so he reached out and said, ‘Man, I think now’s the time.’ The first day we recorded standards and a few covers, but it just didn’t click. It wasn’t inspiring. Theo finally said, ‘Man, let’s just go home.’ So we did.”

“The next day he said, ‘Let’s just play free. We’ll make up some rules—some little devices.’ I remember thinking, Oh, we’re actually going to do this right. He laughed and said, ‘Yeah—just some ideas. You play slow, I’ll play fast. We’ll pick a key and move around it.’ We came up with little games for ourselves. We recorded about 20 tracks in roughly two hours. What came out of it felt very honest. It felt like us. And more than that, it honored where we came from—not just who we are now. I think the industry sometimes puts musicians into boxes: This is what you sound like, so this must be all you do. This project pushed against that. It honored the people we studied with. It honored musicians like Gary Bartz, Wendell Logan, Dan Wall, and Marcus Belgrave—that whole lineage we were raised in musically.”

In regard to the Kurt Elling recording, Fortner recalled how quickly the project came together. “Wildflowers came about through a call from Kurt Elling’s manager, describing how Kurt wanted to start a duo series with piano players. I was asked, ‘Would you be interested?’ I was like, ‘Yeah, absolutely. I’ve never played with Kurt Elling—that sounds fun.’ They said, ‘Great, we’ve got a session scheduled for next week.’ Then Kurt wrote to me and sent a list of about 30 songs, and I remember thinking, I hope he doesn’t think I’m going to learn all of these in five days—that’s not happening. So I learned as much as I could, sent him the list of what I had ready, and we narrowed it down to five or six tunes.”

“One highlight was playing the Fred Hersch tune ‘Valentine.’ I studied with Fred on and off for about five or six years. He’s incredibly honest. If he likes something, he’ll tell you. If he doesn’t like something, he’ll tell you that too—but he has a very particular way of doing it. He can deliver the most devastating critique in a calm, almost gentle way. That kind of honesty—and that kind of care—is rare.”

One of the biggest surprises of Sullivan Fortner’s year, and one of his most enduring achievements, was winning the prestigious Larry J. Bell Jazz Artist Award. “That was definitely a shocker for me. I did not know I was being considered.” The news came by way of a phone call from his agent while Fortner was on tour with his trio earlier in the spring. “They said, ‘When you get to Atlanta, drop your bags off, go to the lobby, and head to the conference room. Everything else will be set up.’ I was like, ‘What are you talking about? Do I have to play there?’” He was told he wouldn’t have to play. “What the hell is this?” he thought, but he followed the instructions.

“I went down to the conference room and immediately recognized several familiar faces. I was like, Oh, okay—what’s going on? Why are you here? Y’all coming to the concert? They said, ‘Yeah, we’re coming to the concert.’ I was like, okay, cool.” Then the moment shifted. “This guy grabs my hand and says, ‘How are you doing, Sullivan? My name is Larry Bell, and I’m associated with the Gilmore Association.’” Fortner’s first instinct was immediate and telling. “I was like, Oh lord, they want me to play something.”

Instead, Bell began to explain. “He said that every year they’ve given this award to classical pianists, and this was the first year they wanted to do something for jazz.” Fortner listened as the story unfolded. “They said they went through a board, and they named the people who were on the board to nominate musicians—all friends of mine, all people that I knew.” What followed caught him completely off guard. “They said I had been nominated and that they’d been scrutinizing my playing, along with others, for about two years. Then they said, ‘We’re pleased to let you know that you are the first jazz recipient of the Larry J. Bell Award.’”

His reaction was equal parts disbelief and composure. “So I’m like, okay—cool. Great. What does that mean?” Then came the explanation of the award itself, including the financial component. “They started telling me about the money.” Asked how he felt at that moment, Fortner didn’t hesitate. “Shocked. I have a lot of questions—like, why me? I still have those questions. But I’m definitely very honored to have been chosen.”

As our conversation unfolded, I asked about his origin story, which began in his native New Orleans, where he was first inspired by the music of the church. Fortner explained, “I actually discovered jazz at church, which surprises a lot of people. I have a cousin who had a high school band called the Mid-City Jazz Ramblers. A lot of the guys in that band went on to do serious things in jazz, and others branched off into completely different styles. For me, being around that band was my real introduction.”

“At church there was a guy named Ronald Markham who was really the turning point for me. One day at choir rehearsal he got on the Hammond organ and started playing Bach. I was like, What is that? He said, ‘That’s classical music.’ Then he said, ‘This is jazz,’ and suddenly he sounded exactly like Jimmy Smith. Then he started playing Latin music, jumping through all these styles. I asked him, ‘Man, how did you learn to play all of this?’ He said, ‘You need to apply to NOCA—the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts.’ When I finally did, I got in—and I couldn’t play a scale. I didn’t know any arpeggios. I knew nothing about classical music, nothing about jazz. All I knew was church, and yet somehow I got accepted. My entire training up to that point was gospel.”

“When I got to NOCA, that’s when I really started studying classical and jazz. The head of the bands and the jazz department was Clyde Kerr Jr., who had taught Nicholas Payton, Irvin Mayfield, and so many others. I was in classes with Troy ‘Trombone Shorty’ Andrews. Jon Batiste and I were practicing together. That was the community. And honestly? I hated jazz. I absolutely hated it. I thought it was too long, too complicated—it just felt like a drag.”

“The very first tune I had to learn for performance class was ‘Giant Steps,’ and I had to learn it in five minutes. Thank God for my church training—I could pull it off—but we played it as a ballad because I didn’t know how to improvise. I just played the chords really slowly. I was 12 or 13 years old. A couple of years later, Mr. Kerr handed me an album and said, ‘This is Erroll Garner’s Concert by the Sea. If you don’t like jazz after this, maybe you shouldn’t be playing.’ I listened—and I fell in love. I don’t know what it was about that record, but it completely changed my perspective. I’ve been chasing that feeling ever since.”

When it came time for college, Fortner initially planned to go pre-med. “I remember having a really heated conversation with my dad after I graduated from high school. He told me, ‘You’re not going to make it by playing music. You won’t be able to make a living. If you become a doctor, you’ll always have a job.’ His message was clear: don’t do music for a living.” Out of dozens of conversations, only a few people encouraged him to pursue music. “One was my mom. The other was a woman I’ll never forget, Veronica Downs Dorsey, who had known me since fourth grade and said, ‘You’ve been playing music for as long as I’ve known you. You’re supposed to be playing.’” Eventually, they convinced his father to let him apply to music school. “So I sent in a video of me playing ‘The Flintstones’ theme to both Oberlin and Berklee. Berklee wait-listed me. Oberlin accepted me—with a partial scholarship. I thought, Well, I guess I’m going to Oberlin. Looking back, it ended up being one of the best decisions I’ve ever made in my life.”

“I promised my dad that if I pursued music seriously, I would at least earn a master’s degree—so if everything else fell apart, I could teach high school. That felt like a responsible plan. So I went to New York and never really left. I started my master’s at the Manhattan School of Music in the fall of 2008. By the spring of 2009, I was already on my first European tour with Stefon Harris & Blackout. I stayed with that band for about a year and a half.”

The next major chapter was working with Roy Hargrove. “Literally right after I landed back in New York from that tour, Roy’s manager called and said that Jon Batiste had double-booked himself with Cassandra Wilson and couldn’t do a month of touring. He asked if I could fill in. We started in Minneapolis, then went to Japan a week or two later, and for several years I was the pianist in his group.”

“As a bandleader, Roy was one of the best I’ve ever worked with. I learned an enormous amount from him. He didn’t talk much and rarely explained things verbally. There was no sheet music—everything was learned by ear. Roy would get behind the piano and play the tune for me first. Once I had it, he’d say, ‘You got it? Good,’ and then move to the drums. Roy could play drums a little, but he preferred to sing the drum parts. While he was singing the drum part, I’d teach the bass player. Once the rhythm section had it together, he’d move on to Justin Robinson on saxophone. That’s how we learned every tune. We almost never rehearsed—maybe two rehearsals in the seven years I was in the band.”

“As a person, Roy was very quiet. He didn’t like big crowds—except when it was time to play music. His main way of communicating with me was through music. He was incredibly intelligent and always reading something, but he was one hundred percent about music. I honestly believe that without music, he wouldn’t have been here as long as he was. I witnessed moments when he could barely stand. Yet somehow, when it was time to perform, something clicked. He found the strength to blow. No matter how sick he was or how his chops felt, he was always musical. Whatever he played lifted the band. Nobody played a ballad like him. The flugelhorn—what he did with that sound—was something truly special. Roy never told us song titles, and he often changed them anyway, so we learned to recognize tunes by the count-off alone. He was one of those rare people who truly preserved a tradition—one of the last bandleaders to keep that way of learning, listening, and transmitting music alive. I miss him deeply. I think about Roy every day and about the lessons I learned in that band.”

Another key association along the way was with Paul Simon. “That came through percussionist Jamie Haddad, who called me and said, ‘Paul’s trying to do a special project with younger musicians, reimagining some of his older songs—songs he liked, but that never really took off the way he’d hoped.’ Apparently, Paul had heard something I played and wanted to know if I’d be interested. The first thing I did was call my mom. I said, ‘Mom, I’m getting ready to work with a Beatle!’ She said, ‘Really?’ I said, ‘Yeah—Paul Simon!’ She said, ‘You idiot. Paul Simon’s not a Beatle.’”

“So I meet Paul at his office in Midtown, and we talk about what he’s looking for. He wanted me to come up with an arrangement of a tune called ‘Some Folks’ Lives Roll Easy.’ One of the rules he laid out was this: ‘If I say it’s interesting, you’re on the right path. If I say it sounds good, you’ll probably never get called again.’ I played the arrangement, and the first thing he said was, ‘Huh. What is that? What song is that?’ I said, ‘That’s your song—Some Folks’ Lives Roll Easy.’ He said, ‘It is?’ Then he said, ‘Interesting.’ I thought, “All right—I’m getting the call. That ended up turning into three songs on that record In The Blue Light (2018-Legacy Records). The last time I saw him was actually last year—we worked on something together then, too. He’s a really great man. Really kind. Very honest. If he likes something, he’ll tell you. If he doesn’t, he’ll tell you that too—and explain why. Then we’ll sit, literally for eight hours if we need to, until it gets to where he’s satisfied.”

Looking ahead, Fortner is energized by what’s next. “I’ve got a new trio album coming out—actually, maybe two—next year. It’s the same drummer and bass player I’ve been working with for the past four years: Kayvon Gordon on drums and Tyrone Allen on bass. One is a studio album, kind of a continuation of the solo record I released in 2023, Solo Game. The other is a live album recorded at the Village Vanguard. That one will probably come out in October. As Fortner continues to balance deep tradition with fearless creativity, one thing is clear: his story is still unfolding, and the music—unmistakably his own—is only gaining momentum.